The following article was published by the Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists in the May 2019 issue of OT Now. Written by Alison Schwartz MSc. OT Reg. (Ont) and Lindsey Schwartz, Physiotherapist and shared to our blog with permission.

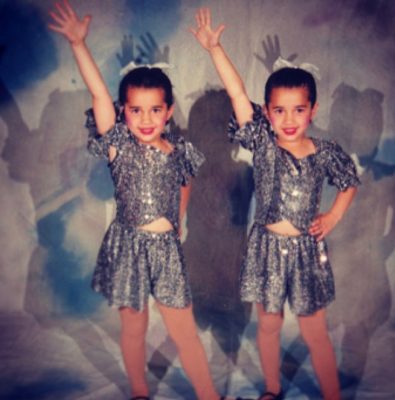

Alison is an occupational therapist and Lindsey is a physiotherapist and both are trained dancers who offer a therapeutic approach to dancing programs at various locations throughout Toronto via Dual Therapy. They also offer their dance program at Toronto Children’s Therapy Center in East/Danforth.

As lifelong dancers, our passion for dance led us to develop an interprofessional therapeutic dance program for individuals with special needs. While completing an international fieldwork placement in Trinidad, we, a student occupational therapist and student physiotherapist, both from the University of Toronto (UofT), had the opportunity to create a dance program that combined occupational therapy and physiotherapy goals. In this article, we will explore our novel interprofessional approach to using dance as a form of therapy.

The use of dance as therapy is an emerging topic of study in the rehabilitation sciences. In addition to the fitness element dance has to offer, there is evolving evidence that dance can provide individuals with additional social, physical, and cognitive benefits (Scharoun, Reinders, Bryden, & Fletcher, 2014). Dance has been shown to increase balance, flexibility, muscular tone, strength, endurance, and spatial awareness for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD; Scharoun et al., 2014). Dance can also improve self-awareness and social communication skills (e.g., empathy, expression; Scharoun et al., 2014). Furthermore, dance can provide physical benefits (increased coordination, strength, endurance, and motor abilities) along with social benefits (increased self-esteem and self-confidence) for individuals with Down syndrome (Becker & Drusing, 2010).

A unique international opportunity arose when we were both placed at the Immortelle Centre for Special Education in Trinidad. The school serves children with special needs up to the age of 18. It also has a vocational centre for individuals with special needs over 18 years of age. For the past 16 years, UofT has been sending student occupational therapists, student speech-language pathologists, and, most recently, student physiotherapists to the school to complete international fieldwork placements. During these placements, UofT students are able to provide therapy services to a population with limited resources and limited access to therapy.

Program structure

During our time in Trinidad, we created and implemented a therapeutic dance program for two groups of students with a variety of developmental disabilities. This program was the first of its kind at Immortelle and was developed in close collaboration with the school’s principal. This process ensured that the needs of the participants were addressed and the appropriate resources were available. Using current evidence on dance therapy, as well as drawing on our own experiences teaching dance, we created a framework and structure for this program. The participants in each group were chosen by the principal and teachers to participate in this program. Each group met for a 20- to 30-minute dance session twice per week for four weeks.

- Group A consisted of six school-aged students (8 to 11 years old). These participants were younger, more physically active, and had higher level cognitive abilities than those in Group B, as reported by the school principal. The goal of running this group was to provide the students with fun, interactive sessions that incorporated therapeutic interventions through the use of music and dance, improving: 1) social interaction, 2) focus/attention, 3) balance, 4) coordination, 5) motor planning, and 6) body awareness.

- Group B consisted of five to seven students from the vocational centre (18 to 35 years old). The goal of running this group was to provide the students with a physical activity program that encouraged engagement and participation, improving: 1) social interaction, 2) focus/ attention, 3) physical endurance, and 4) body awareness. Increasing physical activity tolerances was a priority identified by the school principal for members of Group B, as these students did not have any form of physical activity as a regular part of the school day.

Our ultimate goal was, through working with participants on enhancing skills such as balance, coordination, attention, and social interaction, to also enable them to improve occupational performance in community-based activities and social settings (e.g., engagement in classroom activities, participation in team sports). Sessions with both groups followed a similar structure. Each session began with a warm-up that allowed the students to explore body movements. This was followed by stretches that challenged the students’ balance and range of motion. Activities were incorporated into each session in accordance with the session’s goals—for example, standing on one leg to work on balance. The sessions ended with free dance, when the students could release any remaining energy, followed by a cool-down, which included deep breathing and light stretching.

Outcomes

Over the course of the dance program, in the process of making observational notes, we noticed several changes among the participants. Both groups appeared to become more comfortable interacting and dancing with each other and to become more aware of others as the program went on. Some of the participants with higher level cognitive abilities took on special roles within the group. For example, one student led some of the exercises for her peers, while another student controlled the music. We found that encouraging these roles provided the participants with a “just-right challenge” and helped them to feel engaged in each session. Additionally, participation improved throughout the sessions. In the first few sessions, some group members were hesitant to join the activities and would only observe. As the sessions continued, these students began to join in on the dancing. We noticed that the participants were more willing to follow instructions and participate in exercises when surrounded by their peers, in comparison to during one-on-one sessions. Attention and memory also seemed to improve during the program. As we followed a set structure each session and practiced the same stretches and combination of dance moves, the participants were able to remain more focused and become more comfortable with the movements. As the program progressed, the participants required less physical facilitation and cuing to maintain their focus.

At the beginning of the program, the students in Group B had low activity tolerances. The sessions lasted only 15 to 20 minutes due to limitations on endurance. Toward the end of the four-week program, the sessions for this group lasted up to 25 minutes and participants were better able to tolerate the physical activity.

Challenges

We did experience challenges while implementing this newly developed program. When creating the program, we aimed for a 1:2 instructor to participant ratio. We had fellow student occupational therapists and student physiotherapists help lead the sessions so that each participant could have the attention and support needed to participate. We learned that this ratio was not sufficient for the groups and decided to have 1:1 support for the participants who needed more individualized attention. After implementing 1:1 support for these identified participants, the sessions ran more smoothly. Working with individuals who are nonverbal also involved inherent challenges. However, we learned that one of the great things about dance is that it does not require verbal communication. The participants were able to watch the movements and follow along and participate to the best of their abilities.

Although some aspects of running these programs were challenging for us, we learned an immense amount throughout this whole process. We found that by incorporating the unique interests of each participant in the sessions (e.g., music preferences), as well as focusing on participants’ strengths, we were able to include and engage them successfully, challenging them appropriately and providing the amount of attention they required. Additionally, we learned the power of the group setting. As mentioned, we noticed that the participants were more willing to try new movements, challenge themselves, and focus their attention when they were in a group setting. Participants felt encouraged to participate when they saw their peers following instructions and having fun. The participants were able to learn from their peers and enhance their social skills.

Conclusion

Overall, the program was a success for both groups. The participants enjoyed the program, as we could tell from the smiles on their faces throughout each session. At the end of the program, the participants performed a dance they had been working on during the sessions in the school’s variety show. The participants exuded joy and pride as they performed in front of their family members and friends. As well, the participants’ parents shared how happy they were to see their children perform and be able to demonstrate what they had been working on during the program. This experience has inspired us to further build upon this project in our Ontario community, as we can see the positive impact dance can have on individuals. The next step is to use outcome measures to quantify gains and provide a more evidence-based program. Our goal is to continue using dance as a therapeutic intervention and to further develop this program for a wider array of populations. Our pilot project provided an interprofessional outlook on using dance as a form of rehabilitation therapy and we are excited to see where it can go from here!

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr. Debra Cameron for her support and assistance with this project.

References

Becker, E., & Drusing, S. (2010). Participation is possible: A case report of integration into a

community performing arts program. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 26, 274-280. doi:10.3109/09593980903423137

Scharoun, S. M., Reinders, N. J., Bryden, P. J., & Fletcher, P. C. (2014). Dance/ movement

therapy as an intervention for children with autism spectrum disorders. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 36, 209-228. doi:10.1007/ s10465-014-9179-0

About the authors

Alison Schwartz, MScOT, OT Reg. (Ont.), completed her Master of Science in Occupational Therapy at the University of Toronto in 2017. Alison can be reached at: ali.rose.schwartz@gmail.com

Lindsey Schwartz, MScPT, is a registered physiotherapist with the College of Physiotherapists of Ontario. She completed her Master of Science in Physical Therapy at the University of Toronto in 2017. Lindsey can be reached at: lindsey.mia.schwartz@gmail.com